Have you ever wondered why we have so many different beliefs within so-called Christianity? Why do Catholics believe in Papal Secession? Why does the Church of Christ teach baptismal regeneration? Why do Pentecostals rely on evidence from of salvation from speaking in tongues, miraculous healings, etc.? And, have you ever wondered why all three of these entities have Bible verses to back up their position? Why is that? Why do Baptist shy away from Acts 2 and Mark 16:16?

Is there really an answer to all of this; or are we left to hold to our denominational traditions and just hope we're right come judgment day? If that's the case, there isn't much comfort in that. It also means that I've elevated a denomination above Scripture. So, what can be done? Well, II Timothy 2:15 says, "Study to shew thyself approved unto God, a workman that needeth not to be ashamed, rightly dividing the word of truth." The normative interpretation of this verse is that if we study our Bibles, God will approve of us, we won't be stumped when asked questions (not to be ashamed) and rightly dividing means we will be able to tell right from wrong. Now, this sounds cute, but is this what the verse says? For the most part, yes-but what about the rightly dividing part? What is the word of truth? Well, John 17:17 says, "...thy word is truth." Is God's word ever wrong? So, if God's word is never wrong, how then could rightly dividing mean being able to tell right from wrong? Exactly - it couldn't. So, is Paul telling Timothy that there is a right division of God's word? Well, that's what it says. So, what is this division?

The first division that probably comes to mind is Old Testament/New Testament. Unfortunately, these terms are misleading if you go by the page titles in your Bible. Remember, this division is man-made. In II Corinthians 3, Paul says the Old Testament is synonymous with the Law that Moses gave. When did that Law begin? Genesis 1:1? No-it wasn't until Exodus 20. Now, did the New Testament begin at Matthew 1:1? No - in fact, it hasn't begun yet. The New Testament or New Covenant is completely Jewish (Jeremiah 31 and Ezekiel 36). It is the Covenant that God will make with the House of Israel and with the House of Judah. Even towards the end of Matthew, Jesus commands his disciples to "follow the Law" but just not as the Pharisees do, but in truth. Now, if anything was going to change post-Calvary, why would Jesus make that command only to void it weeks later? In fact, the only thing that had changed come Acts 1 was the fact that Jesus had died and now is risen. Doctrinally, we still stand in the Old Testament. So, you can see that the division of Old Testament/New Testament is really a misnomer.

What about the idea that there isn't a division at all? Many like to take the entire Bible and mix it all together and consume it that fashion. Therefore, they believe that water baptism replaced circumcision and so on. Now, they justify this position with Hebrews where it says that Jesus Christ is the same "yesterday, today and forever", and with Malachi 3:6 where God says, "I change not." What doesn't God change about? Obviously His holiness; His goodness; His justice; His graciousness, etc. No matter when anyone has lived, those attributes of God have not changed. Secondly, has God ever not been God? No, He's always been God, so again, no change. Now let's introduce man-- a free, moral agent if you will. If man has the capacity to make his own decisions, then could God's plan be advanced or hindered by man? Did Adam put a kink in God's plan (as far as Adam knew)? Yes. Did that change God? No, He was still God. This is a poor example, but if God were a square, the borders and angles that are required to be a square can never change (or it's no longer a square). However, does drawing diagonals in the square change it from being a square? Does putting other shapes into the square change it from being a square? No--it is still a square, regardless. So, does input from man's actions and responses to God's change God from being God? No. Therefore, those verses do not defeat the notion of proper divisions in scripture.

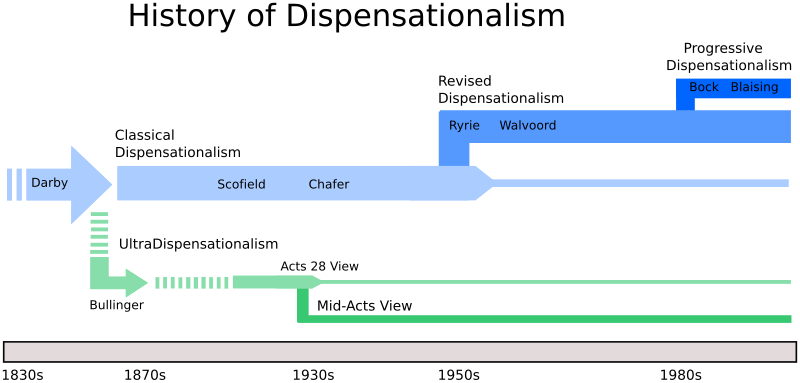

What about dispensational divisions? This is where John Darby and Scofield, etc. come in to play. Note the chart below (from Wikipedia):

Dispensation is a biblical word. Most people believe a dispensation is a period of time. However, dispensation has a root word, dispense. To dispense is to distribute or get rid of. For example, Darth Vader, in Return of the Jedi, arrives at the Death Star and is talking with the Commander. Note the use of the word: "Lord Vader, we are honored by your presence!" "(Vader) You may dispense with the pleasantries commander, I'm here to put you back on schedule." So, in this instance, Darth Vader is using the word to mean "get rid of." There is also a popular candy called, PEZ. PEZ is housed in the PEZ dispenser. Why? Because the dispenser gives out or distributes the candy. Neither of these have anything to do with a period of time. Now, let's look at the entire word, dispensation. Dispensation means a certain order, system, or arrangement; administration or management. So, biblically speaking, a dispensation could be something that is distributing, getting rid of, or managing. And, in actuality, all of these things are happening within a dispensation. God is dispensing His will (distributing); God is getting rid of some former "version" of His will (i.e. His will was to have animal sacrifices under the Mosaic Law, but they are done away with by the death of Christ.); God is then managing by reason of His will. This may or may not be the view of your traditional dispensationalist, but I don't see any other way of defining it.

A basic breakdown in the variants on dispensationalism is taken from http://www.theologicalstudies.org/dispen.html. Any comments by me will be made in [].

1. Classical Dispensationalism (ca. 1850—1940s) Classical dispensationalism refers to the views of British and American dispensationalists between the writings of Darby and Chafer’s eight-volume Systematic Theology. The interpretive notes of the Scofield Reference Bible are often seen as the key representation of the classical dispensational tradition.9

One important feature of classical dispensationalism was its dualistic idea of redemption. In this tradition, God is seen as pursuing two different purposes. One is related to heaven and the other to the earth. The “heavenly humanity was to be made up of all the redeemed from all dispensations who would be resurrected from the dead. Whereas the earthly humanity concerned people who had not died but who were preserved by God from death, the heavenly humanity was made up of all the saved who had died, whom God would resurrect from the dead.” 10

Blaising notes that the heavenly, spiritual, and individualistic nature of the church in classical dispensationalism underscored the well-known view that the church is a parenthesis in the history of redemption.11 In this tradition, there was little emphasis on social or political activity for the church.

Key theologians : John Nelson Darby, C. I. Scofield, Lewis Sperry Chafer

2. Revised or Modified Dispensationalism (ca.1950—1985) Revised dispensationalists abandoned the eternal dualism of heavenly and earthly peoples. The emphasis in this strand of the dispensational tradition was on two peoples of God—Israel and the church. These two groups are structured differently with different dispensational roles and responsibilities, but the salvation they each receive is the same. The distinction between Israel and the church, as different anthropological groups, will continue throughout eternity.

Revised dispensationalists usually reject the idea that there are two new covenants—one for Israel and one for the church. They also see the church and Israel as existing together during the millennium and eternal state.

Key theologians : John Walvoord, Dwight Pentecost, Charles Ryrie, Charles Feinberg, Alva J. McClain.

3. Progressive Dispensationalism (1986—present) What does “progressive” mean? The title “progressive dispensationalism” refers to the “progressive” relationship of the successive dispensations to one another.12 Charles Ryrie notes that, “The adjective ‘progressive’ refers to a central tenet that the Abrahamic, Davidic, and new covenants are being progressively fulfilled today (as well as having fulfillments in the millennial kingdom).” 13 [there are major problems with this position]

“One of the striking differences between progressive and earlier dispensationalists, is that progressives do not view the church as an anthropological category in the same class as terms like Israel, Gentile Nations, Jews, and Gentile people. The church is neither a separate race of humanity (in contrast to Jews and Gentiles) nor a competing nation alongside Israel and Gentile nations. . . . The church is precisely redeemed humanity itself (both Jews and Gentiles) as it exists in this dispensation prior to the coming of Christ.”14

Progressive dispensationalists see more continuity between Israel and the church than the other two variations within dispensationalism. They stress that both Israel and the church compose the “people of God” and both are related to the blessings of the New Covenant. This spiritual equality, however, does not mean that there are not functional distinctions between the groups. Progressive dispensationalists do not equate the church as Israel in this age and they still see a future distinct identity and function for ethnic Israel in the coming millennial kingdom. Progressive dispensationalists like Blaising and Bock see an already/not yet aspect to the Davidic reign of Christ, seeing the Davidic reign as being inaugurated during the present church age. The full fulfillment of this reign awaits Israel in the millennium.

Key theologians : Craig A. Blaising, Darrell L. Bock, and Robert L. Saucy

(WORKS CITED) 1. See Floyd Elmore, "Darby, John Nelson," Dictionary of Premillennial Theology, Mal Couch, ed., (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1996) 83-84. 2. Paul Enns, The Moody Handbook of Theology (Chicago: Moody, 1989) 516. 3.See Craig A. Blaising and Darrell L. Bock, Progressive Dispensationalism (Wheaton: Victor, 1993) 10. 4. These essentials of Dispensationalism are taken from John S. Feinberg's, "Systems of Discontinuity," Continuity and Discontinuity: Perspectives on the Relationship Between the Old and New Testaments, ed. John S. Feinberg (Wheaton: Crossway, 1988) 67-85. At this point we acknowledge the well-known sine qua non of Dispensationalism as put forth by Charles C. Ryrie. According to Ryrie, Dispensationalism is based on the three following characteristics: (1) a distinction between Israel and the church; (2) literal hermeneutics; and (3) A view which sees the glory of God as the underlying purpose of God in the world. See Charles C. Ryrie, Dispensationalism (Chicago: Moody Press, 1995) 38-40. 5. Feinberg, 83.6. Arnold G. Fruchtenbaum, Israelology: The Missing Link in Systematic Theology. Tustin: Ariel, 1994) 118. 7.Feinberg, 85. 8. Blaising and Bock, 21. 9. Blaising and Bock, 22. 10. Blaising and Bock, 24. 11. Blaising and Bock, 27. 12.Blaising and Bock, 49. 13. Charles C. Ryrie, "Update on Dispensationalism," Issues in Dispensationalism, John R. Master and Wesley R. Willis, eds. (Chicago: Moody, 1994) 20. 14. Blaising and Bock, 49.

So, now what? All of these different positions, which one is correct? Or, perhaps, are there other positions? I guess it looks dim for us at this point. In part 2, we'll examine a position not mentioned above. The positions above, generally, suffer from the same problem - they do not follow a pattern of understand the Bible, as it is written. In part 2, we'll see where the Bible gives light into the right division of scripture.